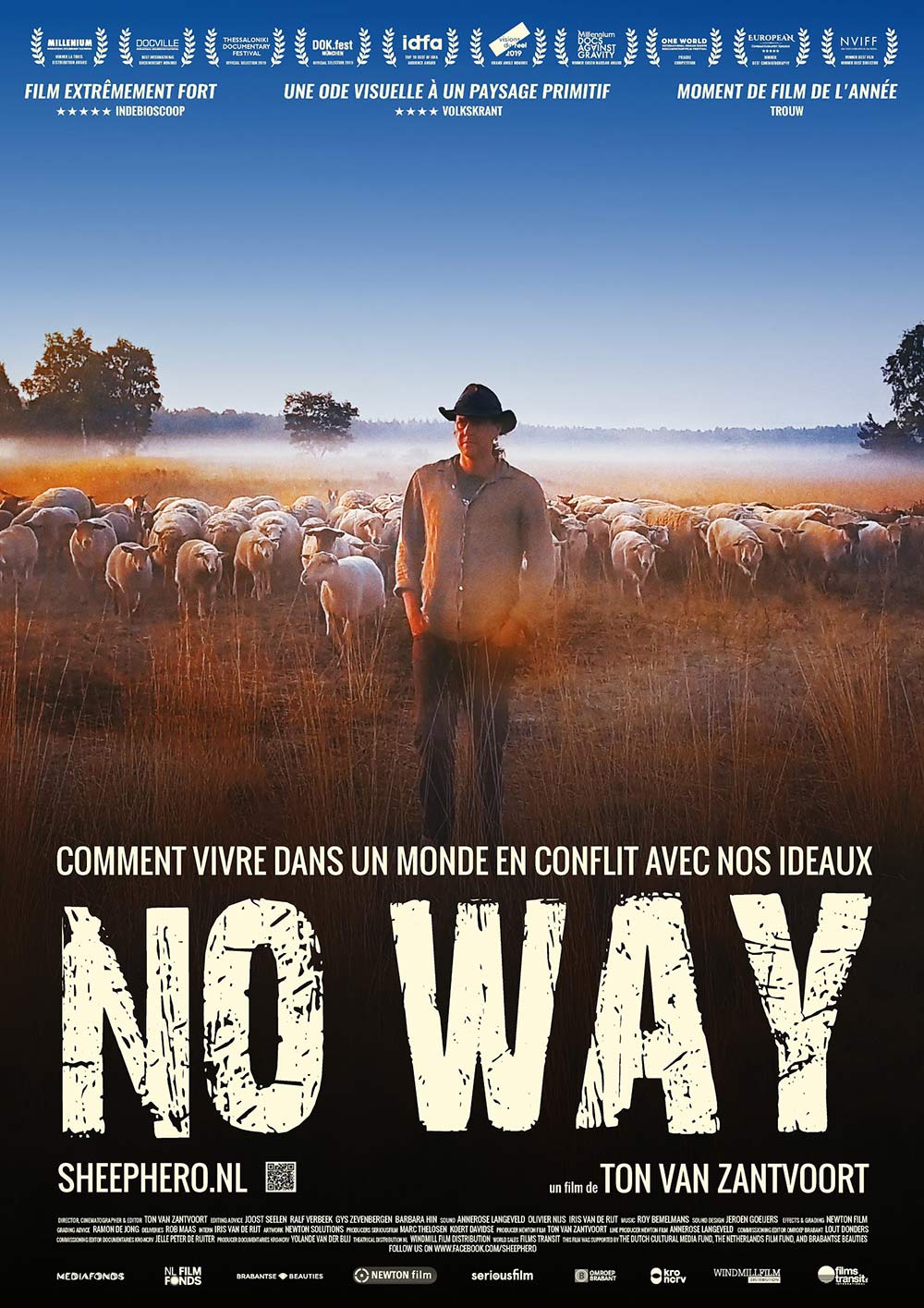

NO WAY IN FRENCH CINEMAS NOW

SHEEP HERO retitled as NO WAY has been released in French cinemas on October 14th. The premiere was in one of the best movie theatres in Paris, the 109-year-old Espace Saint-Michel, that will screen NO WAY already 32 times in the first week only. This week the film also screens up to 7 times Grenoble – Le Club, Strasbourg – Le Star, Marseille – Les Variétés , Chambéry – L’Espace Malraux.

There are also multiple 4 star reviews in national newspapers.

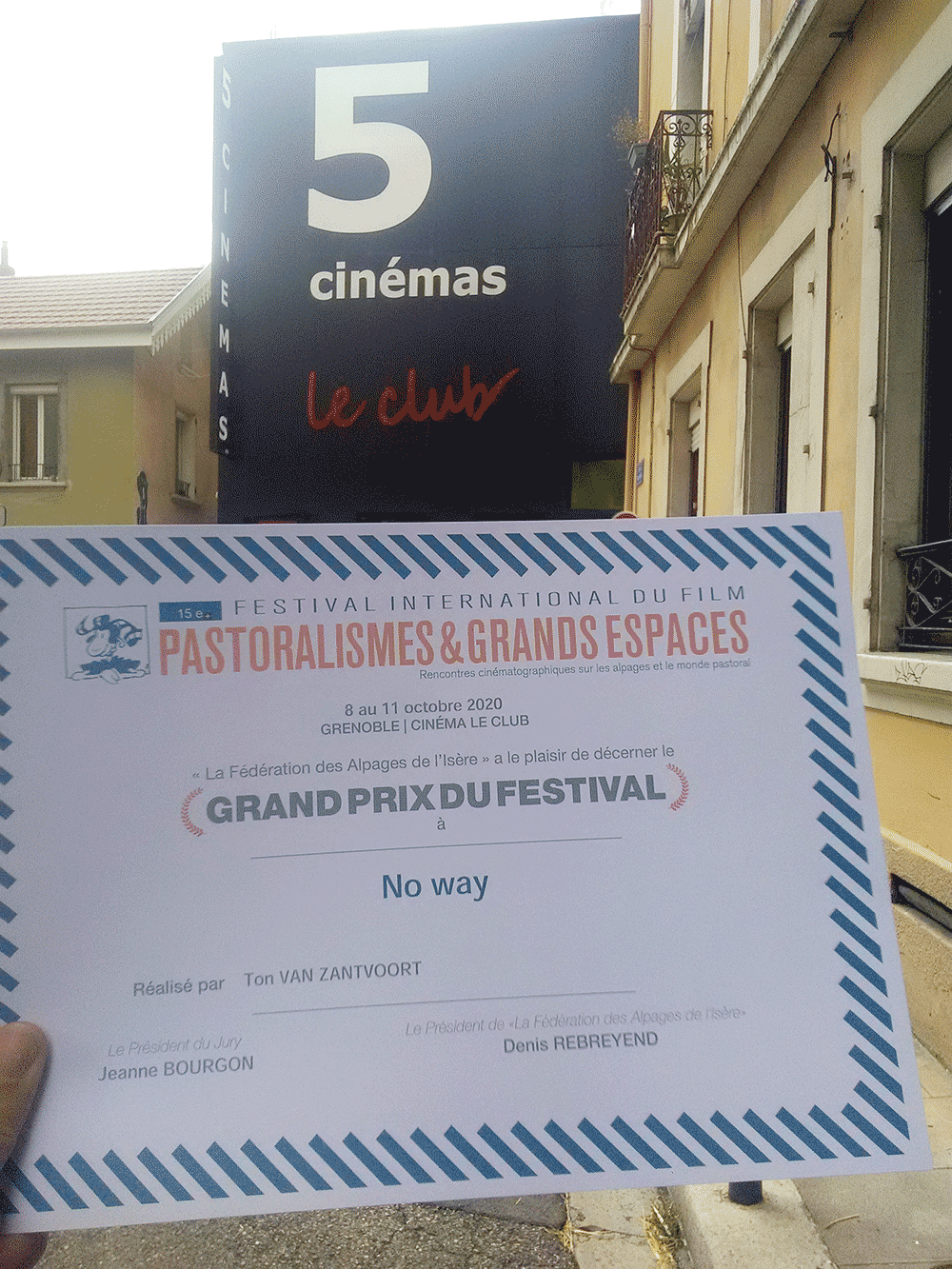

This week NO WAY also won the Grand Prix Award at Le Festival International du Film “Pastoralismes et Grands Espaces”. It is the 24th Award (or actually its first as NO WAY). View all awards on the website

Les Fiches du Cinéma

★★★★ “A documentary of vibrant humanity filmed like a tragic western.”

Ouest France

★★★★

“As with Honeyland, this documentary deals with this subject through the portrait of one of the last Shepherds of the Netherlands.”

Culturopoing.com

★★★ Marjorie Rivière

“Ton van Zantvoort brilliantly accounts for this strong personality who carries the film, wisely using his story to warn more widely about abuses of the system. An essential militant film.”

Le Journal du Dimanche

★★★ par Baptiste Thion

“by its visual beauty and its charismatic cowboy, it offers a beautiful moment of cinema.”

Première

★★★ by Christophe Narbonne

A precious documentary whose melancholy end questions our deep convictions on our way of living and consuming.

Télérama

★★★ by Samuel Douhaire

When the director films (superbly) the sheep in the Dutch moor, it feels like a western.

Grand Prix – Festival International du Film “Pastoralismes et Grands Espaces

Les Fiches du Cinéma by

In the Dutch moors, the mist barely masks the colors of the dawn. In the middle of these landscapes with sublime autumnal hues, we discover Stijn, the shepherd, and his flock of sheep. The memory of these colors, and the tranquility they inspire, permeates the entire film like that of a lost paradise. A stealthy shot shows the fog thickening at the end of a path. We find it at the very end of the film, but the horizon has then definitely disappeared in the gray. It is indeed towards the gray that No Way is heading, that of bitterness which gradually assails the shepherd as he becomes aware of his doomed way of life. Like the Romantic painters, Ton van Zantvoort thus resorts to territory to translate the mood of his main character, whom he most often places in the center of the frame, by playing forcefully on the symbolism of colors (a “degraded color ”is also credited in the credits).

Before being screened on French screens, the film shone in festival under the name Sheep hero, literal translation of its original title Schapenheld. This shift in meaning is indicative of the nuances that make the project so interesting. It is that No Way is first of all the portrait of a man in struggle, who wants to make the world hear his reason. The first third of the story presents an exceptional being, full of humor and tenderness, to the delight of those around him. The “sheep hero” with the physique of Apollo, a little cool (he listens to rock while shearing his animals), shines with the dignity of his art and his atypical life. The film seems to have been thought to embrace his fight: to defend his herd at all costs. But a sequence, located precisely at the moment when a fictional narrative would have found its knot, initiates a shift in our gaze – a reunion that undermines the fragile balance on which the shepherd’s family rests. If you don’t fully understand the details, you get the gist: Subsidies are cut, the herd is in danger, and Stijn’s wife brings up the idea of giving up. From then on, the film becomes the story of stubbornness.

This “No Way” sounds like a challenge addressed to the contemporary world (“there’s no way!”) As much as it coldly announces a dead end. In a sequence at first glance burlesque, the shepherd guides his flock through clean villages, angering the inhabitants. The camera is then as close as possible to this energized figure, whose blue, icy eyes threaten to pierce those around him at any time. Stijn is constantly on the go, smiles and front jokes barely concealing a terrible bitterness of life, and a little too complacent about himself and his living anachronism. We understand then that the filmmaker’s project is less to portray an ecological struggle than to expose the malaise of a disillusioned agricultural environment, in which Stijn’s frenzied enthusiasm appears like a mirage. By dwelling too much on the details of a fight whose outlines we will never fully distinguish, and which can be found anecdotal in our contemporaneity, the film only reveals the full weight of its discourse in the denouement. In a series of sequences with very Houellebecquian cynicism (culminating during the passage of Stijn on the television set of the show “Les Chelous”), Ton van Zantvoort completes in the most eloquent manner the nuanced portrait of this shepherd as a gnawed hero. by fatality.

Culturopoing.com by

No Way. From the title, the tone is set. Dutch director Ton van Zantvoort, used to giving voice to marginalized people who survive by fighting capitalism and mass consumption, this time portrays Stijn, a shepherd who refuses to give up his profession and his ideals for conform to today’s society. This lone cowboy continues to bring his sheep to graze on the Dutch moors in the purest tradition, in the face of massive mechanization. But when he loses his main grazing contract (backhoes are more efficient!), The question of survival arises. How can you continue to feed your home when unfair competition prevents the shepherds from doing their work? “We’re going to have to be creative,” says Anna, his wife and loyal partner.

No Way is not just a film about a shepherd, but the portrait of a man who lives on the margins of society. Charismatic, rebellious and at times unfriendly, Stijn flies the screen. The director, who has known him since 2009, makes him the main character of his feature film, a fighter figure, in a narrative construction close to fiction. “I want the spectators to be able to recognize themselves in this story, in that of my main character,” says the filmmaker, who for this reason wished to integrate into the story scenes of family life taken from life. The marked aesthetic choices and narrative biases participate in the dynamics of this documentary which never ceases to create ruptures, via the alternation of scenes which come into conflict at the same time as they complement each other. First, these sequences, numerous and very aesthetic, in which the keeper leads his herd across the moors. Wide shots, travellings, dives and aerial shots, all means are good to highlight this visually very attractive herd, as well as the majestic and enigmatic landscape, sometimes foggy, sometimes snowy. Pure moments of silence and appeasement, which hark back to an almost bygone era, to that “romantic vision” of the profession of shepherd that Stijn still defends. Then, these sequences of agitation, synonymous with the modern world. Administrative battles, organization of events for the general public to raise awareness of the cause, appearances on radio or television programs, etc., all these particularly eloquent moments refer to the absurdity of the situation. To adapt more and more, to put on a show to make people talk about himself and hope to raise awareness, find money by all means, ever greater daily challenges for this man who only wants to live from what he loves .

Ton van Zantvoort brilliantly accounts for this strong personality who carries the film, wisely using his story to warn more widely about abuses of the system. An essential militant film, which also underlines the incongruity of certain situations with a lot of humor, as evidenced by this scene, at the same time funny and revolting, where a police officer declares: “We have established a report concerning abandoned sheep droppings ”, following a denunciation by residents. Absurdity as a symptom of universal injustice.

original article in French

No Way. Dès le titre, le ton est donné. Le réalisateur néerlandais Ton van Zantvoort, habitué à donner la parole à des marginaux qui survivent en combattant le capitalisme et la consommation de masse, dresse cette fois-ci le portrait de Stijn, un berger qui refuse d’abandonner son métier et ses idéaux pour se conformer à la société d’aujourd’hui. Ce cowboy solitaire continue d’amener ses moutons brouter dans les landes des Pays-Bas dans la plus pure tradition, faisant face à la mécanisation massive. Mais lorsqu’il perd son principal contrat de pâturage (les pelleteuses sont plus efficaces !), la question de la survie se pose. Comment continuer à nourrir son foyer quand la concurrence déloyale empêche les bergers de faire leur travail ? « Il va falloir être créatifs », affirme Anna, sa femme et fidèle associée.

No Way n’est pas uniquement un film sur un berger, mais bien le portrait d’un homme qui vit en marge de la société. Charismatique, rebelle et parfois antipathique, Stijn crève l’écran. Le réalisateur, qui le connaît depuis 2009, fait de lui le personnage principal de son long-métrage, une figure de combattant, dans une construction narrative proche de la fiction. « Je veux que les spectateurs puissent se reconnaître dans cette histoire, dans celle de mon personnage principal », déclare le cinéaste, qui a souhaité pour cette raison intégrer dans le récit des scènes de vie de famille prises sur le vif. Les choix esthétiques marqués et les partis pris narratifs participent quant à eux à la dynamique de ce documentaire qui ne cesse de créer des ruptures, via l’alternance de scènes qui entrent en conflit en même temps qu’elles se complètent. D’abord, ces séquences, nombreuses et très esthétiques, dans lesquelles le gardien conduit son cheptel à travers les landes. Plans larges, travellings, plongées et plans aériens, tous les moyens sont bons pour mettre en valeur ce troupeau visuellement très attractif, ainsi que le paysage majestueux et énigmatique, tantôt brumeux, tantôt enneigé. De purs moments de silence et d’apaisement, qui renvoient à une époque quasi révolue, à cette « vision romantique » du métier de berger que défend encore Stijn. Ensuite, ces séquences d’agitation, synonymes du monde moderne. Batailles administratives, organisation d’événements à destination du grand public afin de sensibiliser à la cause, passages dans des émissions de radio ou de télévision, etc., tous ces moments particulièrement éloquents, renvoient à l’absurdité de la situation. S’adapter toujours plus, se donner en spectacle pour faire parler de soi et espérer éveiller les consciences, trouver de l’argent par tous les moyens, des défis quotidiens toujours plus grands pour cet homme qui souhaite seulement vivre de ce qu’il aime.

Ton van Zantvoort rend compte brillamment de cette personnalité forte qui porte le film, usant à bon escient de son histoire pour alerter plus largement sur les abus du système. Un film militant essentiel, qui souligne aussi l’incongruité de certaines situations avec beaucoup d’humour, comme en témoigne cette scène, à la fois drôle et révoltante, où un policier déclare : « Nous avons établi un procès verbal en ce qui concerne des crottes de moutons abandonnées », faisant suite à une dénonciation de la part de riverains. L’absurdité comme symptôme de l’injustice universelle.