ANIMA will be shown on Monday, November 4, at 23:15 on NPO2 with HUMAN and on NPO Start. Afterwards, the film can be watched again on 2Doc.

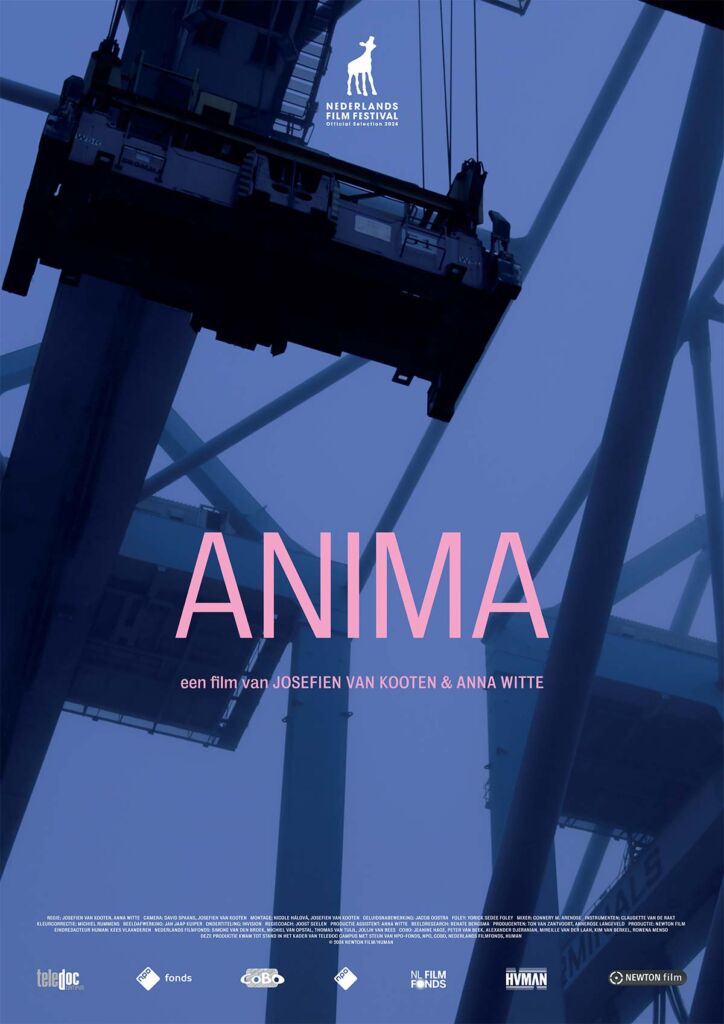

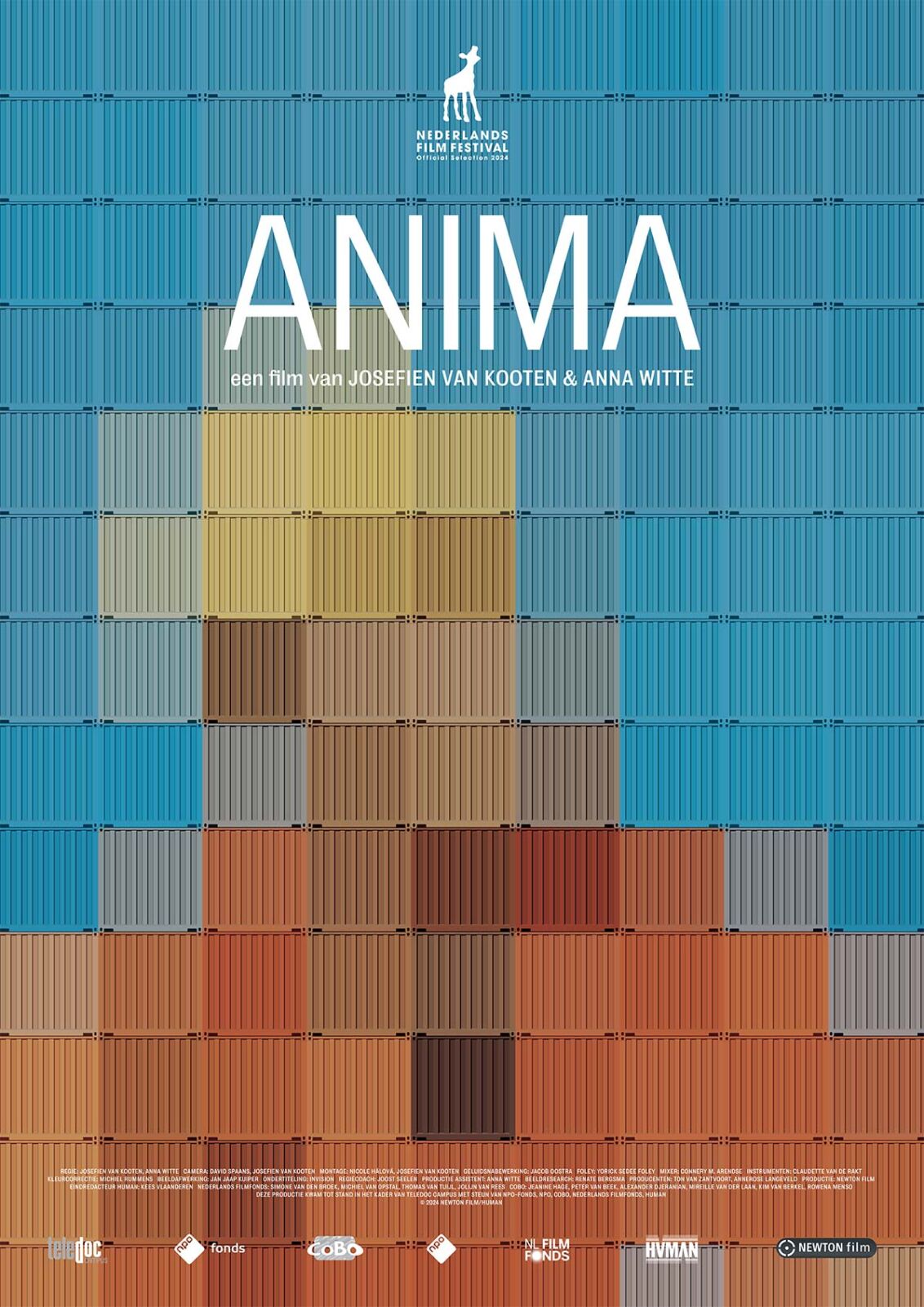

ANIMA, directed by Josefien van Kooten and Anna Witte, takes the viewer into the immense, rhythmic world of the Port of Rotterdam. The film, produced by NEWTON film as part of Teledoc Campus, explores the relationship between humans and machines in this surreal environment, where dockworkers and machines come together as cogs in a grand mechanical network.

Visit the website.

After a successful screening at the Netherlands Film Festival last month, the film received a lot of attention this week in, among others, Algemeen Dagblad, VPRO Gids, VARA Gids, EO Visie, Onkruid, Zin.nl, Broadcast Magazine, and the Filmkrant. In an in-depth interview with Susan Warmenhoven from 2Doc, Josefien van Kooten and Anna Witte shared more about the background and the making of the film, including the challenges of filming in the Port of Rotterdam:

Anna: “Finding the entrance to the port was pretty much the main focus in the making of this documentary.”

Josefien: “It took a year before we got in. It required a lot of perseverance and endurance.”

Anna: “And even when it was arranged, they sometimes canceled anyway. For example, a port company might be implementing an update of their computer systems, and they couldn’t use us during that time. You feel so insignificant with your artistic film.”

The directing duo Van Kooten and Witte emphasize that they wanted to add an “emotional layer” to the film to show the subtle presence of humans. “The contrast between human presence and the indifferent mechanical system of the port was a fascinating starting point. We wanted to capture that anonymous atmosphere.”

In a review for DocUpdate, Helmut Boeijen describes the film as “a living organism, the Port of Rotterdam. Where individual people are nothing more than cogs in a colossal, seemingly smoothly running machine. Task-conscious. Usually working too.”

He praises the careful cinematography with which the filmmakers capture “the anonymous life in the port.” Instead of following concrete main characters, the directors show how each individual seems interchangeable. “The dockworkers are presumably together all day,” Boeijen states. “And there’s a good chance they often feel alone.”

DocUpdate – Helmut Boeijen:

It is like a living organism, the Port of Rotterdam. Where individual people are nothing more than cogs in a colossal, seemingly smoothly running machine. Task-conscious. Usually working too. In any case, hardly any spoken words are heard in Anima (27 min.), the short observational film made by Anna Witte and Josefien van Kooten in this imposing environment.

The two carefully observe tasks that exceed the capabilities of ordinary people. The jobs are mostly carried out by ships, machines, and trucks, with the workers playing only a supporting role. Through small actions, they keep the machine— which seems to know exactly what needs to happen and when—running smoothly.

During breaks, all these workers—hardly a woman in sight—try to maintain contact with the rest of the world. They often rely on screens. Their smartphones, of course, allow them to shift their focus at any unguarded moment. And from the televisions that, unsolicited, provide a glimpse into a parallel world.

Meanwhile, they try to stay in touch with themselves and each other. Through karaoke, for example. Tear-jerkers like “Runaway Train” or “You’re My World” are perfect for belting out together. Or through a game of billiards, where Witte and Van Kooten have placed the camera under the table, so that primarily the slippers and legs of the players are visible.

With careful cinematography, the filmmakers capture the anonymous life in the port. Consistent with this, they also do not choose concrete main characters who become part of their own story. Each individual in this film seems completely interchangeable. Even in reality. The dockworkers are presumably together all day. And there’s a good chance they often feel alone.

Anima is a portrayal of a world in which the individual must hold their own while also remaining human. Characteristic is how a group of dockworkers dressed in orange work clothes and their (female) leader have gathered in an apparently random workspace for a church service. They sing along with a devotional song from a screen.

Longing for inspiration in an apparently soulless world, it seems, which strangely enough still serves that same human being.

2Doc.nl – Susan Warmenhoven

‘What is the relationship of humans to the machines around them?’

In conversation with Anna Witte and Josefien van Kooten, directors of the short documentary ANIMA

In the poetic documentary ‘ANIMA’ (HUMAN), the viewer is immersed in the surreal world of the Rotterdam harbor, where the boundary between human and machine blurs. The editorial team spoke with the directing duo Anna Witte and Josefien van Kooten about the production process.

https://www.2doc.nl/verdieping/artikelen/2024/interview-anna-witte-josefien-van-kooten.html

How did you come up with the idea for a documentary in this universe?

Anna Witte: ‘Years ago, I saw a group of seafarers at the Maasvlakte beach near Rotterdam, who had probably spent months on a large ship. They walked straight into the water, partly still in their uniforms. The contrast between nature and the completely mechanical system world of the port from which they emerged felt very intense to me. I found it fascinating how they became absorbed in that moment. I wanted to understand what kind of life lay behind the world of the harbor: that led to the initial research for ANIMA.’

How difficult was it to gain access to the harbor? I can imagine they’re not really waiting for onlookers.

Witte: ‘Finding the entrance to the harbor was about the main concern in the making of this documentary.’

van Kooten: ‘It took a year before we were inside. It required a lot of perseverance and stamina. We knew we would often hear no, but somehow we also had the confidence that it would work out.’

What exactly is the theme?

Witte: ‘It’s about the relationship between humans and machines. A classic philosophical theme that has already been said a lot about, but we don’t pretend that we are saying something completely new. It takes place mainly in a special, unknown environment.

The film is about how we relate to a world that we have created and designed ourselves, but to which we have also become subordinate. We have to function within that world and its rules. Who is the human in that world, and what makes us human? For us, it was about emotions: longing, sadness, loneliness, and togetherness.’

Witte: ‘And when it was finally arranged, they sometimes still canceled. For example, a port company would implement an update of their computer systems, and they couldn’t use us for that. You feel so unimportant with your artistic film.

But once we were inside, everyone was super friendly and willing. It’s not the people on the floor who hold you back. They want to show how cool their work is and take you up on a crane, for example. Really fantastic.’

Van Kooten: ‘We also went with “Mission to Seafarers,” which is a volunteer organization that sells SIM cards on board. By volunteering with them, we could get on the ships and film there. Still, we could later be rejected: they have to go through a part of the harbor where control is very strict to prevent drug trafficking. So that uncertainty remained.’

Witte: ‘Sometimes we would hear afterwards that we weren’t allowed to film something. So many parties had to be involved, sometimes even during filming. It’s truly the nightmare of every filmmaker.’

Did you know right away that the documentary had to be in a poetic form?

Witte: ‘Josefien and I had made another short documentary together before this one. That was primarily a journalistic and critical essay. Now we wanted to tell the story mainly through images and tap into the emotional layer.

We received a lot of criticism for that; we were constantly asked if there shouldn’t be a character after all. But the search to visualize the theme that was important to us was the greatest motivation to keep going.’

“`

What kind of scenes and images were you looking for?

van Kooten: ‘We wanted to show that there can be a soul in machines, which is also what the title ANIMA refers to: breath, spirit. On the other hand, it had to be clear that those machines are missing that humanity.’

Witte: ‘At the beginning, we were very focused on that. What is the relationship of humans to all those machines around them? Do they become a bit like machines themselves, or do they humanize the machines?’

van Kooten: ‘Just as you can have a bond with your car or computer. Some people even give them names and talk to them.’

Witte: ‘In some images, we knew exactly: here, the human must be very small, and the machine very large. As if you’re standing in a big cathedral. At other times, we wanted to show intimacy between humans and machines. We had already thought of these contrasts at the beginning of the research phase. The images were leading in that regard, which is typical of how we make films.’

ANIMA is not driven by characters. You don’t say: ‘This is Piet, he works in the port, and this is the development he undergoes.’

Witte: ‘It’s not that we didn’t want to know anything about “Piet,” but the story comes from our thoughts about that place and the themes. You can’t expect “Piet” to tell you that story because it might not be in him.

We were focused on the irrational and emotions in a world that revolves around the rational and efficiency. If you ask the people in the terminal: “How do you view these machines, what do you feel about them?” you’ll get answers like: “It’s a cool machine, they are strong.” Then you don’t capture that sensitive aspect in the film. We were interested in details. In one scene, there’s a man in the elevator, and he touches screws in a certain way. There’s a kind of love in that, as if he is caring for something. You can really only show that with images, not with words.’

How did you manage to get the people seen in the documentary to participate?

van Kooten: ‘It was very difficult to organize and predict which people would be present at which place and when. We were lucky a few times, like with that man in the elevator that Anna just mentioned. How he did his work, his entire demeanor: that was a gift. But we had very little control over who we could film and where.’

Witte: ‘You can predict when a ship will arrive, but you never know who will be on board. You have to adjust your way of working accordingly. For us, it quickly became clear that you won’t get to know the people you film very well. You have to accept that and think: this is a good person for the film, this will work on camera, and this person feels comfortable.

We experienced that, for example, with Frederik, the young Filipino man you see lying in bed scrolling on his phone. He was just eager to help us and let himself be filmed. It’s truly a privilege to get so close to someone, especially in a cabin, because they are very private for seafarers.’

What do you hope the viewer takes away from the film?

van Kooten: ‘There are many layers in the film, but I’m never consciously focused on what I want to convey. For me, emotion is very important, and that every time you watch the film, you can have different thoughts about it.’

Witte: ‘I hope people understand that this is a world to which they are connected, even if they may not deal with it in their daily lives. It is the backside of our consumer society. I hope viewers connect with that world and feel something about it.’

“`